TECHNICAL WRITING

Using an expensive model made our agent 75% cheaper

January 19, 2026 · Ben Warren

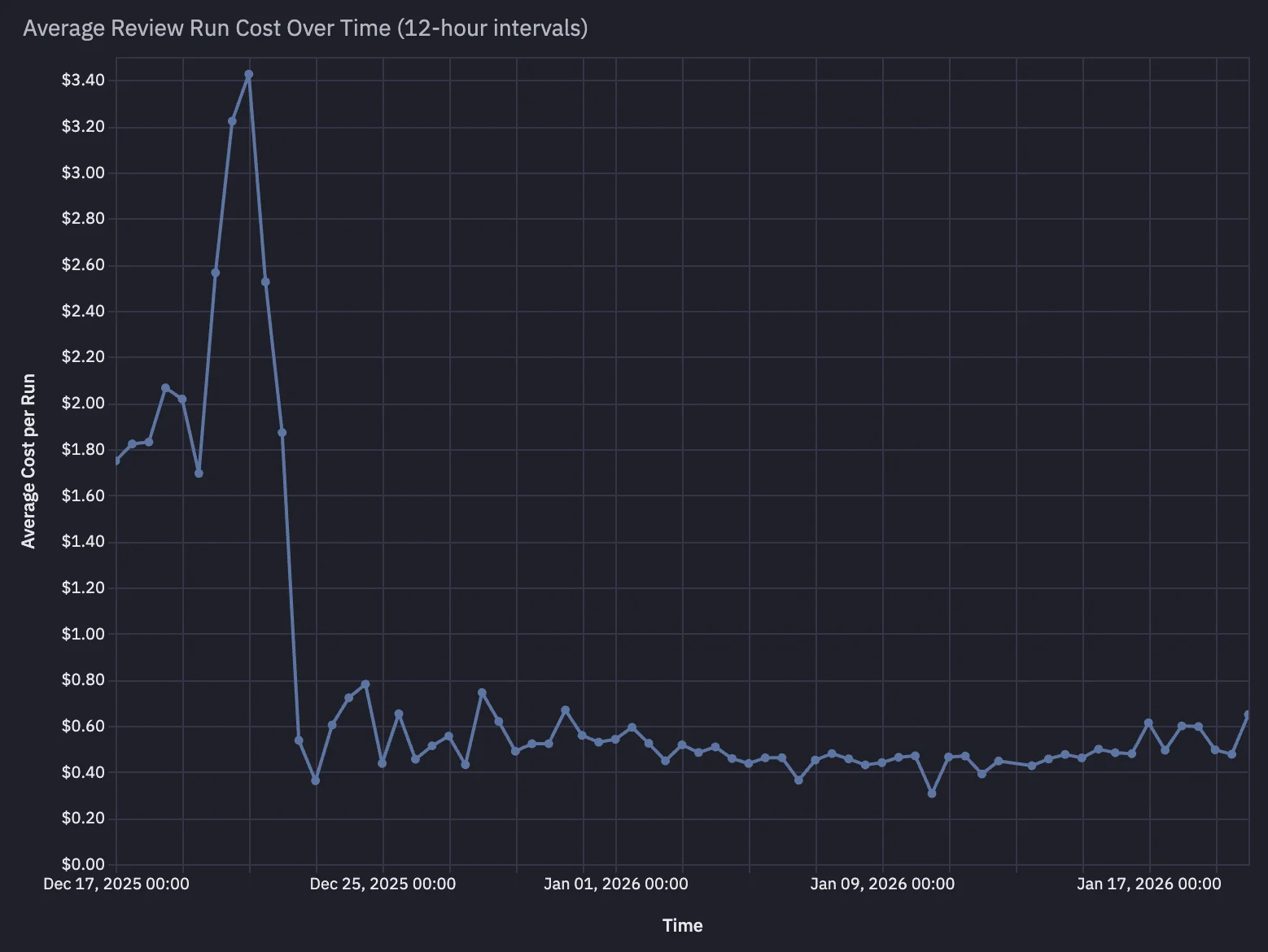

This is the story of how Mesa cut average cost per code review by ~75%, from roughly $2.00 per review to $0.50, by doing something that sounds wrong at first:

We switched to a more expensive model.

This is not a post about model pricing.

It's a post about how we made cost a product metric, built the right instrumentation, and found a lever that reduced cost without guessing.

The moment we realized we had a problem

In December, as hundreds of new companies onboarded onto Mesa code review, we started seeing review costs that were surprisingly high. Some organizations had an average cost per review close to $2.00.

We preempted complaints by adding free credits, but the real requirement was clear: bring down cost fast, and be able to explain why it dropped.

Step 1: Make cost observable at the right granularity

At first, we could see total run cost, but we could not answer basic questions like:

- Are we spending on a single expensive step, or death by a thousand cuts?

- Are we stuck in loops?

- Is the agent making too many tool calls?

- Is cost driven by repo size, PR size, or something else?

So we instrumented the entire review lifecycle into spans and events.

(We originally tried Sentry spans for this, but we ran into missing trace issues and painful joins with org/repo/price-card data. More on why we ultimately built our own system in the next post.)

The only requirement for this phase was: every review run becomes a dataset.

Step 2: Look for the simplest driver that explains most variance

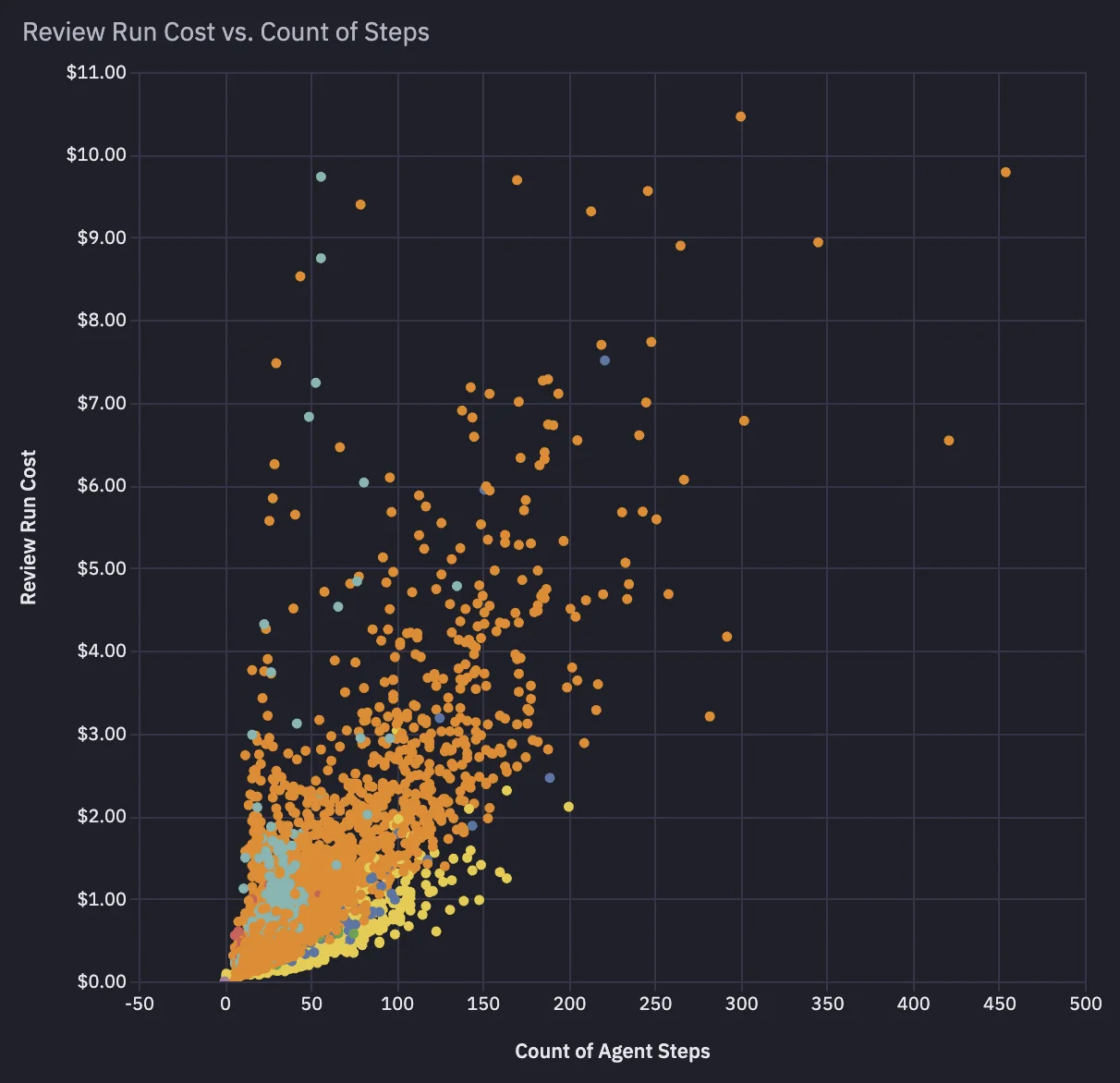

Once we had per-run and per-span telemetry, two patterns jumped out:

- Duration and cost were highly correlated.

- Cost and duration were both primarily driven by the number of steps the agent took to reason through a review.

That shifted our framing:

- We did not need to shave microseconds.

- We needed to reduce the number of steps (turns, tool calls, retries) required to reach a good result.

Step 3: Disprove the obvious hypotheses quickly

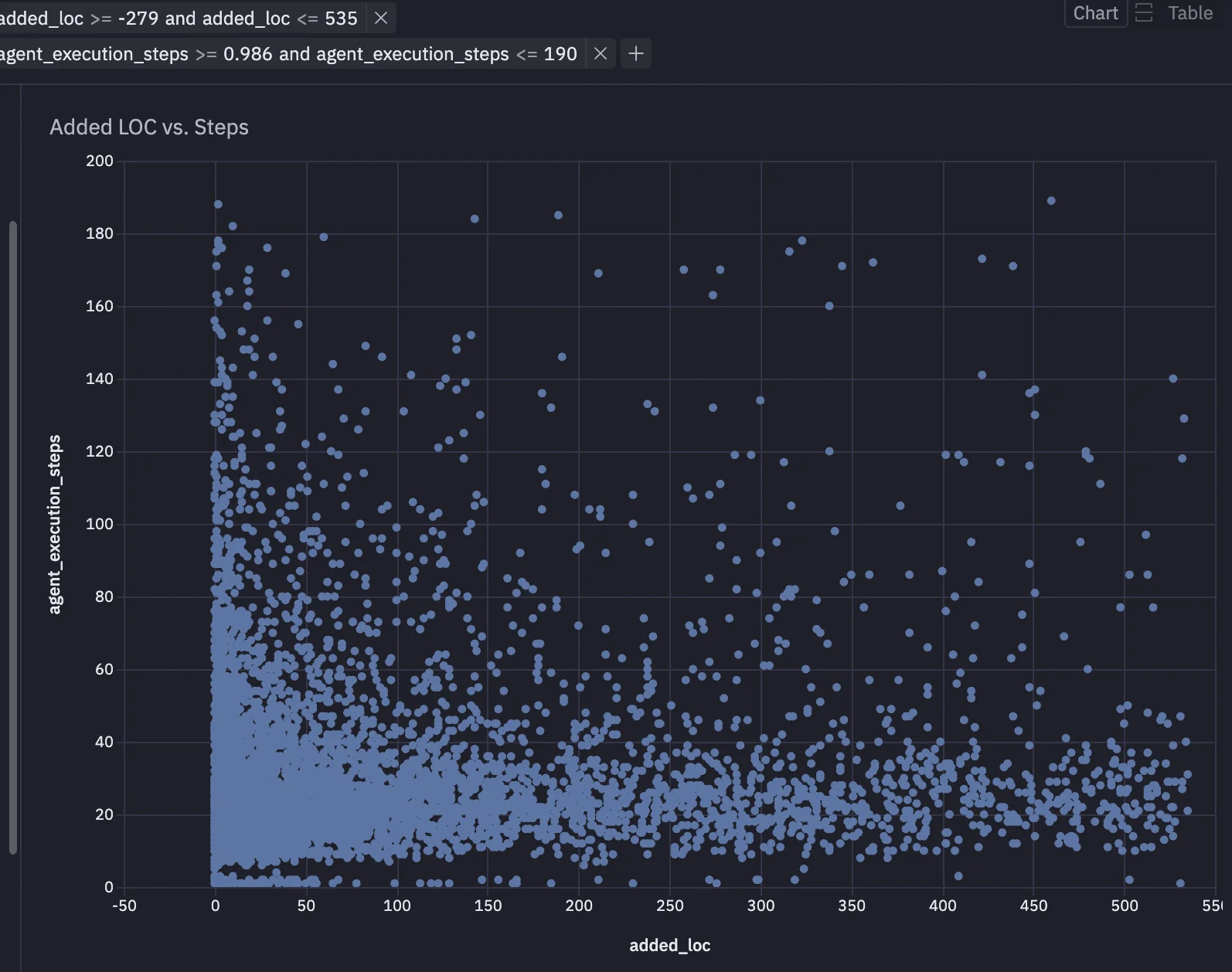

We tested whether review cost was basically a proxy for "how big is the thing".

One hypothesis was that codebase size or PR size drove cost.

It did not.

Step 4: Find the non-obvious driver: model choice

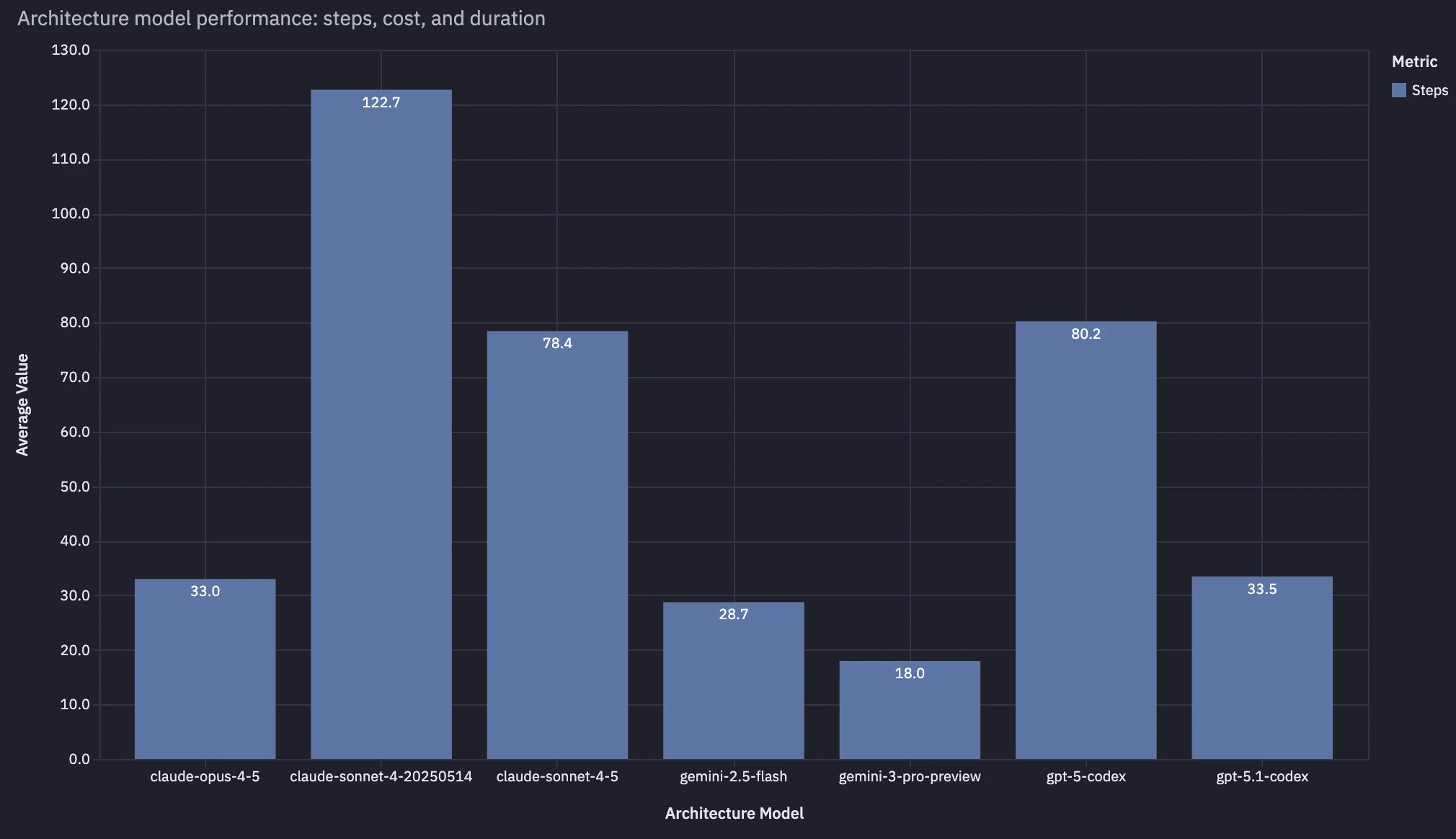

Then we found the strongest result in the whole investigation:

Reviews using lower-cost, "dumber" models were significantly more expensive than reviews using smarter, higher cost-per-token models.

This sounds backwards until you look at step count.

Smarter models were better at:

- finding the minimal relevant code context

- forming a plan quickly

- avoiding tool-call thrash

- converging in fewer turns

Net: fewer tokens, fewer tool calls, fewer steps.

In our data, customers using Claude Opus 4.5 had reviews roughly 2x faster and ~1/2 the price of customers using Claude Sonnet 4.5, even though Opus was close to 2x more expensive per token.

Step 5: Validate with internal tests, then migrate

By this point, we believed the right move was to default everyone to smarter models (for example, GPT 5.1 Codex or Claude Opus 4.5).

Before changing production defaults, we ran internal tests to confirm the relationship held under controlled conditions.

Then we migrated customers and watched the graphs.

Results: ~75% cost reduction

Immediately after the migration, we saw a brief uptick in cost due to cold-start prompt caching effects on first runs.

Then the average cost per review dropped rapidly:

- from roughly ~$2.00/review

- to roughly ~$0.50/review

What actually changed (the mechanism)

The important part was not "we picked a different model".

The mechanism was:

- step count dropped

- which drove duration down

- which drove total tokens and tool calls down

- which drove total cost down

Lessons we'll keep using

- If you want a cost reduction you can defend, start with instrumentation, not opinions.

- Most of the time, cost is a function of iterations, not a single line item.

- In agentic systems, paying more per token can be cheaper overall if it reduces step count.

What's next

In the next post, we'll go deep on the observability decision: why Sentry wasn't enough, what we built in a day, and what it unlocked once all the telemetry lived in Postgres.